A Message From Beyond the Grave

“Who do you think you are? Don’t get too big for your britches, young lady.” This is what she seemed to be saying.

“Wait, what?” I heard myself think. She even used the scolding phrase, young lady. Twice. She was talking to me like a mom who’d earned the right.

It was a jarring travesty—a parenting blasphemy.

One minute I was a relatively copacetic, integrated, mature, capable woman taking care of my aging parent, and the next, it’s late summer between middle school and my freshman year of high school—confused, ashamed, isolated, terrified:

Yesterday I was at my parents’ home in Northern California. My mom’s a little wobbly these days and so as she was finishing up in the powder room, I sat in her vanity chair on the other side of the pocket door, waiting for her to finish up so that we could get back to the couch and continue watching the usual suspects of daytime TV.

The two never-before-seen (by me) letters penned by my birth mother and one court document had serendipitously landed in my lap. It was an abrupt pull back in time, a sudden jerk from one reality into another, ala Twilight Zone. As though someone had picked up tiny me with a set of massive salad tongs, extracted and pulled me way up into the universe, and then dropped me back down in another world, or at least another time. And I can’t put my finger on the movie, but I can see a flash of it—a moving image: a scene in blurry, high-speed reverse—someone is being sucked back in time, through a funnel-shaped tunnel. The person’s arms are reaching forward in resistance, but the pull is too strong, and they’re defenseless in a futile fight against the suck. As I read through the letters, it was a psychic discombobulation, one minute it was 2020 and the next, 1976, and I’m confronted with someone I did know and didn’t know. With a snap of the fingers, 44 years was gone, and I’m a child being scolded by an entitled, shaming mother who’d never mothered me.

And now in this bizarre, unexpected moment—via time capsule—I’m introduced to a new side of my biological mother, one that could be cruel, one that that I never knew existed.

Am I allowed to say that out loud?

I’m still working through that question in my life. One of my favorite Anne Lamott quotes is: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” I sometimes—strike that—often, have trouble with this ownership. This minute, not so much. If ever I had the deed, I have it now.

Addressed to me by certified mail—one dated September 4, 1976, and the other September 23, 1976, the letters must have been intercepted by someone protecting me, someone who had tucked them away in a drawer with other “important papers,” hoping that I’d never see them. Historically—because I silently hated them—I had either ceremoniously burned or thrown out everything else my biological parents sent me over years until they died, and if I would have seen these letters, these would have been no different. They’d be embers. That was my MO: Torch ‘em.

Based on the document from the Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles Juvenile Court, dated August 2, 1976, these letters were written the following month after a hearing we’d been summoned to and attended because after abandoning me at 18 months old, my biological parents were attempting to regain custody of me. I guess at 14, they were good and ready to have me come “home,” which was—to my thinking—the height of impudence.

What she said in these letters was her response to what I had said aloud in that traumatizing Los Angles courtroom.

Because of the initial blur from the Twilight Zone/highspeed reverse time funnel, It took three readings to begin to decipher what she was saying to me. When I began to get my bearings, I heard—through my now differentiated, evolved adult mind—her blatant projection, obfuscation, denial, delusion, blame. All of it intended for the child she professed to love.

It wasn’t all new information, exactly.

I had spent my life hearing at least most of what she’d said in these letters, but in all those years, she said many of those awful things with a weirdly palatable twist. She sprinkled sugar on the shite. Accompanied by that mortifying, cringy smile, the confusing message made it all the more damaging to me. It made me question my own goodness and sanity.

She, along with my biological father, would routinely threaten (to them, “reassure”) me that we’d “all be a family again,” that I was a Cole through and through, never, ever to be a Ciarolla (and what I deeply wanted). “You’ll never be free of us,” she’d said in many and not so many words. They put their backs into convincing me who I really was, and I tried desperately to disbelieve them, to fight the suck.

I was a privately rebellious, succumbing ball of conflict—thankful, grateful, indebted; fearful, guilty, ashamed all the time.

After those first three reads of the letters, some fog cleared, and the courthouse flashes of memory came. I remembered what I’d said in court: that the Ciarollas were my real parents and asked a rhetorical “who were these Cole people and what had they ever done for me in thirteen years?!” I told the judge that if the court sent me back, I’d run away. I think those three words sold it that day.

And so, these two letters are evidence of how much that day hurt her.

For the first time, I was exposed to—may I say it?— a creepy side of her. The side that could rage, could create more chaos in a heart, could guilt a child for a parent’s failures.

From the chapter “The Bio-illogicals,” in The Little Love That Could:

“I have a visceral memory of having to go to court when I was fourteen. I was horrified. HORRIFIED! I remember sitting across from them in the cold hallway at the Los Angeles County Courthouse. I could literally see Elsie’s heart pumping in her chest. I wanted to look away, but I couldn’t not look. It was like viewing a car accident.

The judge asked if I wanted to go back to live with my bio-illogicals, and I said emphatically, “I DO NOT, and if you send me there, I will run away.” As timid as I was, I didn’t have to muster a “Bring it!” attitude. It was an organic, don’t-mess-with-me, I’ll-walk-this-talk absolute. I meant it as much as I’d meant anything in my fourteen years.

Elsie died two years later. Robert died five years after that. They both passed early due to heart-related ailments. They died of broken hearts is my best guess.

I had monster nightmares about them growing up, though during our visits I remained a very polite little girl who never told them what I really wanted to say. Their choices, however, wreaked havoc. Up until my late twenties, I hated them for what they’d done.

Even after I’d stopped blaming them, it took me a long time to sever myself from the umbilical cord of shame. I thought I would be forever tethered to them. I imagined myself floating around in space like George Clooney in Gravity . . . but attached to the shuttle of Robert and Elsie. My bruised body would keep smacking against their hard surface, more and more battered with each collision.”

~~~

Yesterday, out of nowhere, I smacked against their hard surface—again—this time from a full-fledged, verbal/emotional smack-down by a mother-by-a-technicality who pretended to know me, outrageously assumed a right and authority she was never even close to having.

It seems clear her main intention was to burst my fantasy balloon that I’d ever be rid of them, and that I’d ever be a Ciarolla. To shame me into loving her/them.

Reading these letters for the first time, 44 years later, I see how effective she was with the sweeter, more confusing, cloaked version of that message throughout my young life. How it reverberated long after she died. I still heard her voice, saw that smile, and she was right—she did haunt me. She did the job. But she was never successful at shaming me into loving them.

There is a silver lining here, the surprise gift in having read these letters now: Validation. It was real. I didn’t imagine it. I wasn’t “overly sensitive,” or silly. She’d communicated the message all along on a lower frequency, but the message came through loud and clear.

I could never change who I was.

The letters were more than a tad “schizophrenic,” In one line, jealousy of my affection for the Ciarollas, and the next, gratitude for the Ciarolla’s kindness. These letters were emblematic of how delusional she was.

I’ve heard the writerly advice by Crystal Woods: “Write like no one is reading.” If a writer is to write authentically, they ought to write like it’s a journal entry. I’ve often censored myself in order to protect others in my story. Sure, sometimes it’s to protect myself, but mostly, I don’t want to out anyone by “airing dirty laundry,” or be accused of oversharing—sharing something someone else might deem too private. I do think there’s an appropriate balance. I think it’s okay to hold some things back. But as I’ve learned, if you do reserve details, you will be criticized for that, too.

Hence the Crystal Woods quote.

Those “dirty laundry” details—the most dramatic, sometimes controversial, provocative juicy bits are where life is lived. It’s not about being sensational, it’s about being authentic. It’s where the beauty and the ugly and the pain and the healing intersect—and sometimes if we’re lucky, the redemption.

There is a tremendous value—a service—I think, in showing the gritty space: the struggle while questions are not yet answered. When the repair work is incomplete, and there is no shiny bow on a professionally wrapped package. I’ve personally benefited from others’ willingness to show the painful, unresolved process. If all we see from others is the scrubbed and sanitized, hermetically sealed version of life (the clean laundry), we don’t help each other along the way, we’re not truly in a healing community. Ram Dass wrote, “We’re all just walking each other home,” and if we want to take hold of one another’s hand on that walk, we need to be willing to show the real life.

My biological mother never knew the work I would do to differentiate from them. She never knew the layers upon layers of healing there’d be. And based on the surprising impact these two messages from beyond the grave have had on me—the healing still to come.

I don’t know if there were more certified letters intercepted—tucked away, still to be found, or maybe tossed by someone else with an MO: Someone actually doing their best to look out for me, protect me, love me—mother me.

I used the word compromised earlier: “I was torn between two realities and identities and perpetually compromised and confused.”

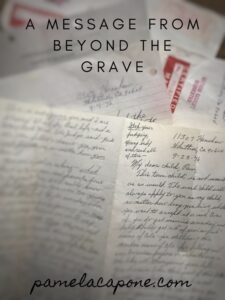

I’m going to compromise by showing an image of the letters but blurring most of her words.

It’s hard for me to want to see her with empathetic eyes right now, to imagine how that would have felt to hear what I’d said in court.

I may get there. But I’m not going to do that right now. I need a minute.

“Who do you think you are? Don’t get too big for your britches, young lady.”—said a mother who wanted to mother, who did not mother, who was unable to mother.

There’s no bow tied up at the end of this writing. I’m getting ready to give the letters a fourth read to help understand who I think I am–because, after all, she asked.