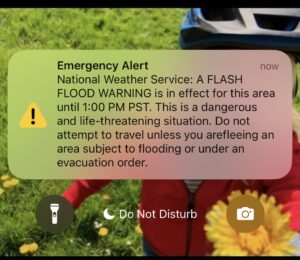

I hear the whirlwind whip, the pummeling, relentless rain, and the sudden, extended chime on my phone: the National Weather Service warning me of flash flooding.

It’s been “flooding” for a while over here, guys. Maybe where you are, too.

I look back down at my computer and re-read the two quotes I’ve copied and pasted into a document in a folder I have titled “Good Mourning.” Both quotes recently caught my attention and both of them happen to use the word “blooming.” Two places, same word. Surround sound. So I pay closer attention.

The quotes:

- “This is the urgency. Live and have your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.” – Gwendolyn Brooks

- “The Shadow of Private Pain: There are other factors at work that obscure the free and unfettered expression of grief. In the chapters above, I pointed out there those of us who live in the West are conditioned to accept the notion of private pain. This cultural conditioning predisposes us to maintain a lock on our grief, shackling it in the smallest concealed place in our soul. In our isolation, we deprive ourselves of the very things that we require to stay emotionally vital: community, ritual, nature, compassion, reflection, beauty, and love. Private pain is a legacy of the creed of rugged individualism. In this narrow story, we find ourselves caught in the shadow of the heroic archetype. We are conditioned from birth by the image of the hero, the one who needs no one, the one who rises above his or her pain, the one who is always in control and never vulnerable. We are imprisoned by this image, forced into a fiction of false independence that severs our kinship with the Earth, with sensuous reality, with the myriad wonders of the world. This is a source of grief for many of us. Facing the sorrows of the world requires that we remain intimate with the world. In my practice some years ago, I worked with a woman who was deep in grief about the war in Iraq. She wept and wept about the land being poisoned by fragments of bombs made with depleted uranium. She cried about the hundreds of thousands of civilians killed or wounded by the assault. After sitting with her for some time as she cried, I asked her if she had noticed the plum blossoms that were blooming outside the window. She paused and said, ‘No.’ I asked her if she had noticed the mustard in bloom. Again she replied, ‘No.’ I then said to her, ‘We cannot face the horrors of Iraq with any sense of balance without also remembering the beauty of the world — the plum blossoms and mustard blooming.’ We must couple grief and gratitude in a way that encourages us to stay open to life.”—Francis Weller

Weller’s words immediately reminded me of the Pema Chödrön quote I love (see graphic at bottom).

And Ram Daas’ suggestion about keeping our hearts open in hell.

The point is not to deny the pain or the rain or the tiger or the hell and just bright-side yourself to death while wearing ridiculous, plastic rose-colored glasses. Grief and gratitude are not mutually exclusive. After all these years and tears, how do we not know that? Weller’s words advise against private pain—that Western idea of buck up, buddy. Many of us are drowning in the flood of buck up, buddy.

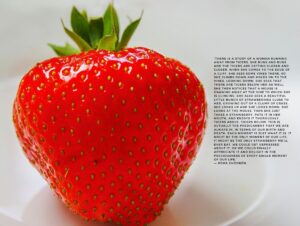

With tigers above, tigers below—the idea is to keep our hearts open in hell, our eyes open to plum blossoms and mustard blooming, to pluck the juicy strawberry and taste the sweetness, tune into the sound of the rain, inflate a dinghy for the flood, and out of the shadow of private pain and into the light of community, care and love from above, daring to trust in the future bloom.

*“There is a story of a woman running away from tigers. She runs and runs and the tigers are getting closer and closer. When she comes to the edge of a cliff, she sees some vines there, so she climbs down and holds on to the vines. Looking down, she sees that there are tigers below her as well. She then notices that a mouse is gnawing away at the vine to which she is clinging. She also sees a beautiful little bunch of strawberries close to her, growing out of a clump of grass. She looks up and she looks down. She looks at the mouse. Then she just takes a strawberry, puts it in her mouth, and enjoys it thoroughly. Tigers above, tigers below. This is actually the predicament that we are always in, in terms of our birth and death. Each moment is just what it is. It might be the only moment of our life; it might be the only strawberry we’ll ever eat. We could get depressed about it, or we could finally appreciate it and delight in the preciousness of every single moment of our life.”–Pema Chödrön